Food System Vision Prize

How might Colombo, Sri Lanka imagine healthy, sustainable food futures for the year 2050?

CHALLENGE

While attending the African Green Revolution Forum in September 2019, I met someone from OpenIDEO who described his work on the Food System Vision Prize over lunch. The Rockefeller Foundation — in partnership with Second Muse and IDEO — was welcoming communities from around the world to “envision regenerative and nourishing food futures for 2050.” Their goal was to encourage people to come together and formulate collective visions of positive food futures, as opposed to the “doom and gloom” narratives we more often hear.

A few friends from the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) — Felix Thiel, Ilsa Philips, Nikita Drechsel and myself — initiated a Visioning process in Colombo, Sri Lanka in our spare time. We assembled a core team of people highly active in Colombo’s food system and helped facilitate their community outreach ideas, such as attending food-related events and hosting our own Visioning event. Finally, we drafted a Vision, which was iterated over and ultimately approved by the core team.

Everywhere we went throughout this process, from a university to a landfill to a startup incubator, we asked people: What would you like Colombo’s food system to look like by the year 2050?

PROCESS

1. To gauge interest in developing a Vision for Colombo, we pitched the Food System Vision Prize to several people who are highly active in Colombo’s food system. While we IWMI individuals were personally intrigued by the Food System Vision Prize, we did not want to impose our own Vision upon the city’s residents. We invited a few contacts from our local circular economy projects to KIKU, one of the most sustainable cafes in Colombo, and asked whether they’d like to co-facilitate a Visioning process. These included Erandi Narangoda of the Soup Bowl, Hanzalah of Sri Lanka’s Robin Hood Army, Savera Weerasinghe of Ananta Sustainables and Jackie of KIKU. They agreed with enthusiasm and we got down to work!

2. We began attending food-related events around Sri Lanka and interviewing attendees about their needs, values and aspirations. In order to tap into current discourse around Colombo’s food system, we kept an ear to the ground and started showing up to events and key locations after work and on weekends. Between November 2019 and January 2020, we listened and asked questions at:

Manning Market in Pettah, the biggest wholesale market for fruits and vegetables in Sri Lanka, which is located in Colombo.

The International Water Association’s Water and Development Congress, which took place in Colombo in December 2019. Here we heard from Sri Lankan government officials who spoke at the conference, as well as students presenting their research. For instance, Anil Dissanayake, Secretary of the Ministry of the Environment said, “Sri Lanka’s per capita emissions are negligible but climate change is severe for tropical islands like us.”

Demo Day for six sustainable food-related startups that went through the Good Life accelerator program at Hatch, an incubator in Colombo. The entrepreneurs pitched their products for potential investors, including a hydroponics startup called Honest Greens, a treacle startup called Kimbula Kithul and Savera’s company Ananta Sustainables, which produces 100% compostable packaging.

Kaduwela Landfill, which houses a composting plant and participates in Sri Lanka’s waste management project. Here we learned about existing efforts to recycle and reuse waste via the Pilisaru project, as well as the potential of rural-urban linkages for waste management.

The Saturday Good Market in Colombo, where responsible businesses and social enterprises sell their products weekly in a parking lot next to Colombo’s Racecourse. These range from hand-made batik clothing to books to locally grown and packaged organic foods, like cashews, honey, pickled items and fruits and vegetables. Participating vendors described their personal stories that led them to a Vision of an economy that’s good for both people and the planet.

A workshop called “Business of overcoming climate change impacts in agriculture and the food supply chain,” hosted by the Netherlands Embassy and IWMI. In 2019, the Global Climate Risk Index ranked Sri Lanka #2 on its list of 176 countries most at-risk of climate change. This event welcomed farmers, researchers, government officials and business people — including representatives from both supermarkets like Keells and wholesale markets like Pettah — to discuss adaptation strategies.

AgriTech 101 at the University of Jaffna. In an impressive student-run initiative, the University of Jaffna’s agriculture students kicked off their semester by inviting farmers to present their challenges and insights, so they can develop demand-driven research topics and technologies. First, several speakers — including Ilsa, Nikita and me! — addressed the students to frame the event. Farmers then discussed their issues and ideas: pest management, vermicompost (using worms to compost), crab culturing, kitchen gardens in Jaffna, reducing kitchen waste in Jaffna, lack of guidelines for transitioning to organic agriculture and more. Students and faculty members broke out into groups based on the issues raised and worked with the farmers to investigate paths forward.

Our core team also had prior experiences with the food system in Colombo and Sri Lanka more widely. For instance, Erandi and Hanzalah both run their own food NGOs; Savera organizes a Trash Talk series and runs a company that produces compostable food packaging from agricultural waste; and Jackie strives to make KIKU a sustainable, community-centered cafe. From IWMI’s team, Felix has managed projects on resource recycling and reuse in Sri Lanka for the past five years. Personally, I had spoken with farmers in the dry zone about their challenges for a project rehabilitating parts of Sri Lanka’s ancient tank system, led by IWMI researchers Mohamed Aheeyar, Herath Manthrithrilake and Lal Muthuwatta. I’ve also gone to the Nattandiya area with IWMI researcher Simon Langan and SenzAgro CEO Miller Rajendran to learn how coconut plantations have adopted SenzAgro’s IoT sensors and mobile app for automated irrigation scheduling.

3. We read up on Sri Lanka’s reports, plans and policies regarding agriculture, urban development, climate change and more. An understanding of the country’s national development goals — thanks to documents like the Sustainable Sri Lanka 2030 Vision and Strategic Path, National Adaptation Plan for Climate Change Impacts in Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka National Water Development Report and Sri Lanka National Agriculture Policy — helped us contextualize people’s lived experiences and hopes for the future. They also suggested the direction in which the country as a whole hopes to go.

4. We hosted a Visioning Event with our core team. In December, we invited people who work across Colombo’s food system to join our core team in envisioning the future of Colombo’s food system: farmers, investors, policy-makers, entrepreneurs, students, NGOs, hotel and restaurant employees, retailers, etc. Around 20 attendees gathered one evening after work.

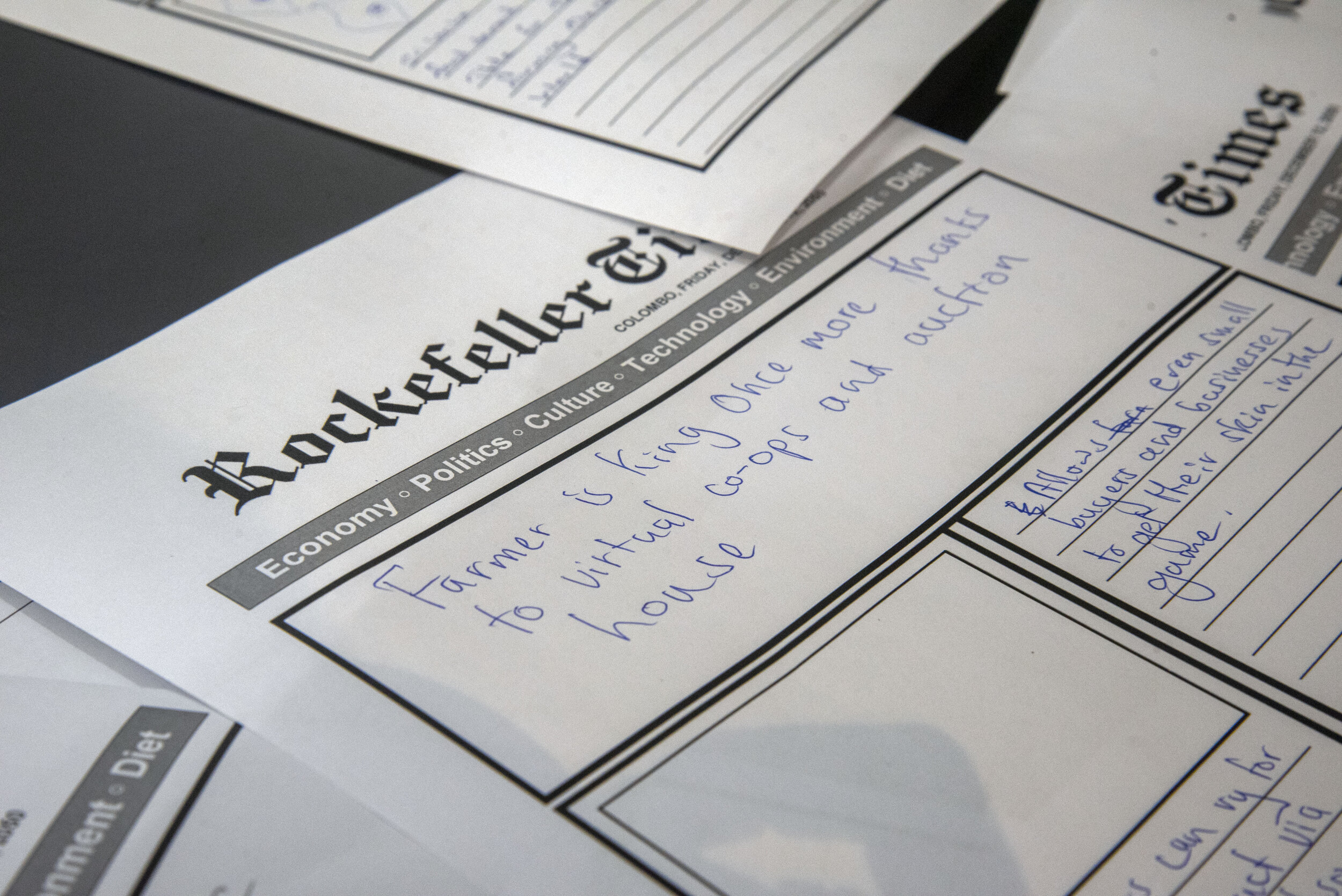

First, Felix introduced the Food System Vision Prize. Then, Savera skillfully facilitated four activities: 1) food system values mindmap, 2) identifying current factors that shape Colombo’s food system, 3) categorizing the aforementioned factors — and any additional ones — in a game of “Keep, Start, Stop” and 4) writing news headlines from the future.

The evening ended with the exchange of many business cards and ideas for cross-fertilization across sectors, which was great to see. We were especially happy about the intergenerational turnout and how invitees brought their loved ones — we had one mother/daughter pair and one brother/sister pair show up.

5. We synthesized our notes and drafted the Vision in an iterative process, getting feedback from participants and final approval from the core team. The IWMI team synthesized our notes from attending food-related events, reading Sri Lanka’s food-related plans and policies and listening into the conversation at the Visioning event. We shared our notes on the Visioning event and a post-event survey with participants to welcome any additional thoughts or corrections. We shared all notes with our core team members for feedback. Next, we prepared a first draft of the Vision, held a writeshop with the core team for feedback, prepared a second draft of the Vision, shared it with the core team, received their approval and submitted it to the Food System Vision Prize. The full text of our final Vision can be found here.

LIMITATIONS

Representation. We wish that we could have included more food producers, like the pig farmers who collect waste in Colombo, in our Visioning process. The language barrier posed a big problem for us here, since we were unable to approach non-English speakers in Manning Market, on farms or at the waste treatment sites. This resulted in us reaching mostly wealthy residents of Colombo who spoke English.

Lack of time. We also had many ideas that we were unable to complete due to the short Prize timeframe. For instance, we thought about going into kindergartens or primary schools and asking students to draw a picture of their dinner plate in thirty years — what would they be eating?

Disengagement with politics. Politics can be a sensitive topic in Sri Lanka and we were unwilling to put participants in an uncomfortable position by prompting a political discussion, unless they raised the topic themselves. As a result, the Vision does discuss some future policies for Sri Lanka but does not offer much constructive critique regarding past or present policies.

Dominant perspectives. No community is homogenous; and this (word-limited) Vision captured the dominant perspectives of the people represented. For example, a few people talked about how colonialism and the Green Revolution transformed farming practices in Sri Lanka. The former replaced ancient growing practices that emphasized a diversity of crops with tea plantations. The latter increased farmers’ dependencies on high-yielding seeds and chemical fertilizers, turning them away from native varieties. One woman spoke of the nutritional benefits of returning to a traditional Sri Lankan diet, despite all the Western-style cafes cropping up across Colombo. Another woman raised concerns about land use in Sri Lanka: namely, how people are encroaching upon elephant territory to expand their agricultural lands. While some of these ideas were touched upon in the final Vision, we weren’t able to capture or describe all marginalize perspectives.

NEXT QUESTIONS

Having completed the Visioning process, how might a community sustain its momentum and go from Vision to action?

With heterogeneity in mind, how might a collective Vision reflect the diversity of Visions that people may have for their community? For instance, within our conversations, we frequently saw a tension between people who believed returning to tradition was the best way forward and people who believed embracing technology and innovation was the best way forward. A plurality of Visions may be necessary to reflect a community’s range of ideas and concerns, rather than one Vision. This calls into question at what scale Visioning should take place.

Our Vision didn’t make it to the semifinalist round of the Food System Vision Prize. We were disappointed — especially when we had to break the news to our core team — but we knew the competition would be steep all along; and either way, it was exciting to see so many Visions for healthier, more sustainable food futures. However, then I took a closer look at the semifinalists. After receiving 1,318 Visions from six continents, 26 out of the 79 semifinalists (33%) were from one country: the United States. I was originally really enamored by the bottom-up model of the Prize: a donor was asking communities what they aspired to and then providing them with funding to bring their aspirations to life. After seeing the overrepresentation of semifinalists from the United States and Europe, I’m now a bit more disillusioned. Hundreds of teams from the Global South put in unpaid time and labor to generate ideas for the Rockefeller Foundation in the hope of winning institutional support and funding, but ultimately received no credit or financial support. Teams from the Global North did the same, but so far have disproportionately received the recognition of making it to the semifinalist round. Now I’m left wondering: how might donors support communities in self-determining their futures in an equitable, non-extractive process?

This participatory visioning project was facilitated by me, a Digital Innovations Analyst at the International Water Management Institute, and Felix Thiel, a consultant at the International Water Management Institute. Our core team included Erandi Narangoda (the Soup Bowl), Hanzalah ____ (Robin Hood Army) Ilsa Philips (IWMI intern), Nikita Drechsel (IWMI intern), and Savera Weerasinghe (Ananta Sustainables). Jackie of KIKU generously lent us her space to use for our meetings.